A quick review of architectural photography reveals a curious fact. Rarely are people shown inhabiting the spaces depicted and when they are present, they usually appear as mere props, subordinated to the real topic of interest.

At the recent launch of Zahah Hadid’s Chanel Pavilion, Chanel Creative Director Karl Lagerfeld was recorded on camera saying, “Sorry there are so many people. It looks better with nobody.” Do such sentiments indicate a lack of interest on the part of architects and sometimes their clients, for the lived experience of those inhabiting their buildings?

There may be systemic reasons that encourage neglect of the user within the architectural profession and their sponsors. Architects tend to be judged by other architects so the opinion of the user counts for less. “Design awards are given primarily for imagination and originality at the expense of the users’ health, happiness and well-being,” argues Byron Mikellides, Professor of Architectural Psychology at Oxford Brookes University. “Corporations and others like to select these high profile personality architects,” says Stewart Brand in his documentary series “How Buildings Learn”, “and then you want them to make a statement. Very often their statement has very little to do with the actual use of the building.” The enduring image of the architect as artist unencumbered by evidence-based research and user-centred design continues to weaken the connection between architects and inhabitants.

TOP-DOWN ARCHITECTURE

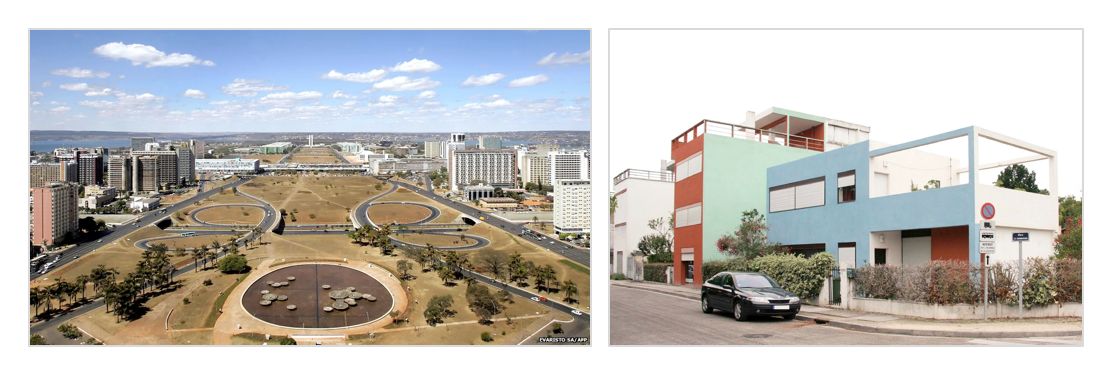

The history of modern architecture is replete with examples of grand visions enacted by architects that have resulted in ineffective and alienating environments. Take the example of Brasilia as a whole city, its desolate spaces well depicted in Gary Hustwit’s documentary “Urbanized”. In Europe, Le Corbusier, founding figure of modernist architecture, sought to impose his utopian vision for modern society only to find that the incoming residents of his buildings, such as those at Pessac, had other ideas and soon adapted their homes to suit how they actually wanted to live. Rarely, however, do architects conduct post-occupancy evaluations on their structures, perhaps to avoid sullying themselves with the mess that usage and everyday life will bring on their buildings.

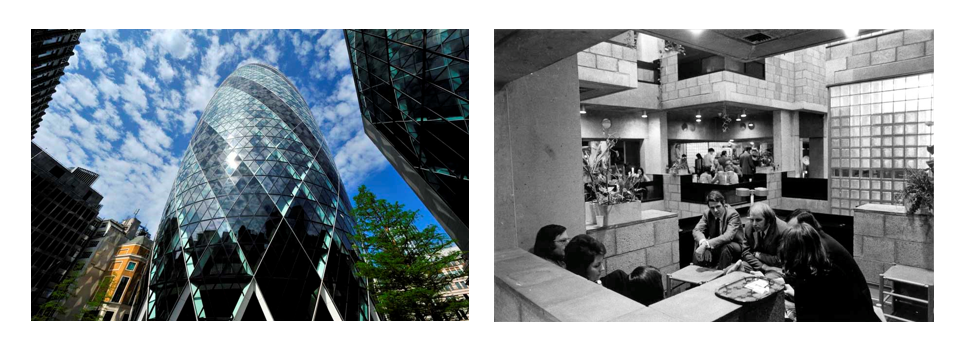

The BBC documentary Architecture at the Crossroads charts the legacy of modernist architecture on our built environment. First aired in 1986 and currently available on BBC iPlayer, the programme focuses on failed attempts at social housing such as Maiden Lane and Alexandra Row in London; places apparently rejected by their inhabitants. In so many cases the architect’s aspirations appear to have been out of step with those of the residents, who were not consulted.

“One suspects that these buildings did not grow out of a desire to come to a more complex relationship between the inhabitants and their building, but out of a desire to advertise, to be interesting.” bemoans the narrator.

THE SECRET LIFE OF BUILDINGS

The documentary series “The Secret Life of Buildings“, written and presented by architectural critic Tom Dykhoff and aired by Channel 4 in 2011, provides an entertaining and rare focus upon the user experience of buildings. Dykhoff brings Sir Norman Foster, architect of London’s Swiss Re building (better known as The Gherkin), face to face with the people who use his building every day. While the building has a spectacular exterior, much less consideration appears to have been given to an interior which, from the accounts of workers within the building, offers a rather bland and unsatisfying experience.

As a point of contrast, Dykhoff looks to examples from The Netherlands and Germany where architects such as Herman Hertzberger have championed the role of the inhabitant in their buildings, designing spaces from the inside out rather than the other way round.

CAN ARCHITECTURE MAKE US HAPPIER AND HEALTHIER?

By neglecting the user when designing built space, are we missing the chance to impact positively upon our well being? Can good architecture make us happy, as popular philosopher Alain de Botton argues in his book “The Architecture of Happiness?” At a time when positive psychology is becoming increasingly popular in both academia and the media, it is perhaps not surprising that some architects, such as those involved with RIBA’s Building Happiness project, are now beginning to take these questions more seriously.

“Order attracts order, beauty attracts beauty.”

My interest in the user experience of designed space was originally sparked by the writings of psychologist James Hillman, who argued that we ignore the psychological effects of built space to our detriment. Psychologists should engage with cities, buildings and schools rather than focusing solely on people’s inner lives, he believes.

When I was in Barcelona more recently, I took a guided tour around Hospital de San Pau, built in the 1920’s and 30’s and now a World Heritage Site. “What does this place look like to you?” asked our guide. “A monastery.” I said. “A Disney theme park.” suggested another. It certainly looks like no other hospital I have seen and must have been guided by very different principles from the 1930’s brutalism that inspired the hospital building I was born in.

San Pau’s architects believed that a beautiful and carefully designed environment could assist in the healing process of its patients. “Order attracts order,” our guide told us. “Beauty attracts beauty. If a place looks beautiful, then patients can relax.”

Our guide’s assertion that ‘order attracts order’ might be dismissed as pure speculation if it were not for research that is now beginning to back up this intuition. In The Dirty Streets Project, Dutch researchers (now working in the UK government’s ‘nudge group’) set up two conditions in a Dutch city street, one of order and the other of disorder. Flyers were attached to bicycles parked in an alley. In the first condition the alley was free of graffiti and litter. In the second condition, graffiti was added to the walls and litter to the street. When cyclists returned to their bikes, researchers found that when the alley contained graffiti, 69% of the riders dropped their leaflets on the floor compared with 33% in the alley where the walls and floor were clean.

Researchers have found that beautiful surroundings can inhibit the experience of pain (amusingly illustrated by Dykhoff in his documentary). Maslow and Mintz found, in a classic study, that the attractiveness of an environment had an effect on how people are perceived. Subjects who spent 10-15 minutes rating a series of facial photographs in a beautiful room rated the faces as having significantly more energy and well-being than did subjects tested either in an average or ugly room.

In The Secret Life of Buildings, Dykhoff visits Kingsdale Foundation School in London, a school that has seen a significant rise in attainment levels following a re-design of the architectural spaces within the school. Prior to the redesign, every floor and door in the building looked identical and corridors were too narrow for the number of pupils moving around the building. The space was opened up, providing larger communal areas through which pupils can walk to their next class. Colour was used and geometry on a human scale was applied in an attempt to de-institutionalise the space. Following the redesign, behaviour in the school calmed, exclusions went down from 280 a year to almost 0, and the number of pupils achieving at least 5 GCSEs rose significantly.

In an engaging TED talk, acoustics expert Julian Treasure makes a further plea for architects to pay more attention to the experience of inhabiting interior spaces. As a sound engineer, he argues that architects must design less with their eyes and more with their ears. That many currently do not is evident when spending time in a restaurant that looks wonderful but in which it is difficult to hear the person across the table from you. Or classrooms where bad acoustics prevent effective learning amongst pupils and increases stress levels in teachers.

ENVIRONMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY AND NEURO-ARCHITECTURE

Given the obvious inter-relationship between designed space and the users of a space, it is surprising that the field of Environmental Psychology has thus far had a very limited effect on architecture. Methodological issues, together with architects’ reluctance to engage with such research, seem to have limited its impact.

The architectural school at Oxford Brookes is one of the few institutions that teaches ‘Architectural Psychology’ to its trainee architects. Lead Professor Byron Mikellides concedes though that ‘there is little evidence that it is taught, let alone integrated [elsewhere] within the architectural curriculum in the UK.’

While the psychological study of built space may still be struggling for recognition, neuroscience is opening a new front on our understanding of human responses to the built environment, that may yet impact the architectural profession. Using virtual environments that can be easily manipulated, neuroscientists at The Institute for Place and Well Being are measuring how our brains respond to our surroundings. The hope is that this neurological understanding will encourage the design of buildings that support the functioning of its inhabitants.

“Architects are impacting the structure of my brain by virtue of the designs they are making, but they are not taking into consideration how.”

Scientists at Salk Institute for Biological Studies have shown that a stimulating environment can actually encourage growth of new neurons. ”Architects are impacting the structure of my brain by virtue of the designs they are making,“ says Salk Institute Professor Fred Gage, ”but they are not taking into consideration how.” If architects work with neuroscientists it may be possible to build environments that optimise our performance.

“To ignore [user needs] is to perpetuate the view that architecture is only an art,” argues Professor Mikellides, “rather than the process of articulating form which reflects human life and emotion.”

There are signs of a growing awareness of evidence-based design amongst architectural bodies. As the evaluation of user experience becomes increasingly valued for the benefits it brings to the design of everything from websites to services, perhaps architects too will come to recognise the benefits this perspective can bring to their profession and, through their buildings, to us all.

With the growing integration of digital capabilities into built space, perhaps we, as interaction designers and user experience practitioners, will find ourselves in useful dialogue with architects as our future spaces are conceived and constructed.

Want to learn more?